Okay, it’s been a minute since I’ve been here on the old blog. Time goes quickly – didn’t realize it’d been over two months. But will be trying to update more often as we go forward.

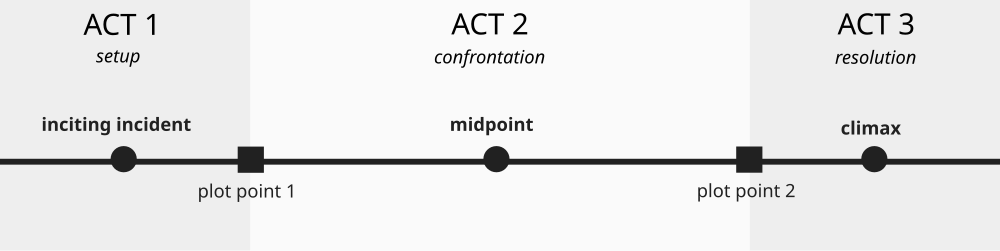

Since I’m getting back to basics with my blogging (yeah, that was some gratuitus aliteration), I thought I’d cover the three act structure for screenplays, which is something that you’d hear about on the first day of any screenwriting class. However, it’s deceptively simple, and often misunderstood.

For starters: The three act structure is something that virtually every film with commercial value employs, at least to some extent. There are obvious exceptions – usually the so-called art films, which employ little if any conventional structure and therefore aren’t worth considering when discussing… well, structure.

But even within commercial films, you’ll often find a litany of exceptions. Ron Shelton, who wrote and directed Bull Durham, often states that the film doesn’t have a third act. I kinda/sorta disagree, but at the same time, it’s hard to tell a writer he’s wrong about his own movie. Horror films often feel more like two-act films than three… a build towards a massive change at the midpoint, followed by an accelerated second half of a film in new and often, well, horrific circumstances. From Dusk Til Dawn and Psycho both feel this way.

Okay, enough equivocating. Here is how the three act structure works.

ACT ONE

Roughly the first 25% of the film. During Act One, we are introduced to our hero, and we see the circumstances at which they start the story – good, bad or indifferent. Ideally, we’d see most if not all of the background on our characters and circumstances that we’d need to follow our character or characters on ther upcoming emotional journey. That’s called exposition. We like some exposition for our characters, but as the story has not actually begun, you have to be careful about giving too much, because you’ll bore your audience.

Then, inevitably, something happens that knocks them out of these circumstances. That’s called the Inciting Incident, and this is the point where the story begins. The Inciting Indident can take place anywhere within the first act – from the opening seconds of the story all the way until the end of the first act, or the First Act Break. Rocky, for example, which won Best Picture in 1976, used a very simple story structure that combined the First Act Break and the Inciting Incident into one story beat – it was roughly at the 25% point of that film that Rocky was put on his path towards the boxing match with Apollo Creed. Though I would caution that today’s audiences are more impatient than they were 50 years ago, and starting a story 25% of the way into the movie may not be the best idea.

Another change that has to be considered is the effect of franchise films like those of the Marvel Cinematic Universe. Avengers: Endgame has one of my favorite opening scenes of all time – a two-minute stand-alone scene which shows Hawkeye (Jeremy Renner)’s family disappearing in Thanos’ snap, which brilliantly re-anchors the audience in the emotional stakes of the ending of Avengers: Infinity War the year before. However, the film then essentially does a 20-minute extension to the ending of Infinity War. Endgame doesn’t actually start its first act until the “Five Years Later” appears on the screen, and the film’s Inciting Incident is when Ant-Man reappears from the Quantum Realm.

This leads us to the Act One Break. This is the end of the first act, and a significant story beat. This is where your character decides to leave their comfortable world and start in on the journey that defines the rest of the film. Think of Luke Skywalker accompanying Obi-Wan on his mission.

ACT TWO

The second act is the longest part of any film, and comprises the half between the 25% and 75% points in the story. The pace may ratchet down a shade as we settle in. This is also where a lot of good screenplays get killed – it’s often tough to keep the attention of your audience and come up with a lot of solid scenes, even if we have a great beginning and/or ending.

One of my screenwriting professors taught me about a story-beat here that I like: The “Holy Shit” moment. This is a near-immediate reversal that comes directly after the Act One Break. This is used to amp up the stakes for our main character, or perhaps introduce a not-previously-seen force of antagonism for the hero.

The next major beat is the midpoint of the film. This can go in a variety of different ways, but it usually takes on the form of a major scene in the film where the hero must (a) double down on their mission, which results in (b) increased stakes. For example, in Christopher Nolan’s Inception, this is where DiCaprio’s character learns that he and his team can be killed inside dreams, whereas before they would just wake up. DiCaprio, of course, proceeds with this knowledge, though not without some significant anxiety for both himself and us.

For my own writing, I tend to break Act 2 up into two parts: 2A and 2B, with the midpoint acting as the break between them. 2A for me is often a slower pace, while 2B increases both pace and tension as we head down the back half of the movie. As I previously mentioned, a lot of films change significantly at their midpoints. Psycho, for example, changes main characters after Norman Bates kills Marion. From Dusk Til Dawn completely changes film genres at its midpoint, morphing from a slow, gritty crime character drama into a batshit crazy vampire movie.

No matter how you employ your midpoint, the second act will culminate in the Second Act Break. This goes by a few different names, including the All is Lost moment and the Dark Night of the Soul. This is where your main character suffers a major setback and may actually quit their journey entirely, returning to the comfort of the world they knew before the movie started. Often, it’s a major character death – such as Obi Wan in Star Wars: A New Hope or Black Widow in Avengers: Endgame. This leads your characters to question their entire mission and despair.

ACT THREE

Much like the “Holy Shit” moment in the early part of the second act, there is a moment in the early third act that gives your character a sliver of hope. The timing on this is much more flexible than the holy shit reversal, however. It largely depends on how long you need your characters to mope around, or if you need time for the antagonists to shift their pieces on the board.

Either way, once you hit that reversal, your main character is now on a collision course with the end of their mission and/or the antagonist. Think Luke Skywalker meeting the Emperor in Return of the Jedi while Lando and the rebels attack the Death Star.

This brings us to the climax. This is the final “battle” in your film, which is often an actual battle, like in Star Wars or any Avengers film. Sometimes, it’s a quiet confrontation, like Gordy and Chris standing up to Ace and his gang in Stand By Me. But no matter your story, this is the moment that your character or characters will have to marshal all of the lessons and development they’ve gone through during the course of the film and push themselves beyond everything they ever thought before. The culmination of the film shows how your characters have changed throughout the film.

What happens after that varies by the film. Some movies end quickly – North by Northwest, for example, has something like 47 seconds after the final battle at Mount Rushmore, just enough to show the main characters running off together. Star Wars: A New Hope has the famous medal ceremony (where Chewie gets screwed out of a medal for some reason). Avengers: Endgame has nearly 10 minutes, showing Tony Stark’s funeral, Thor’s moving on, Captain America’s surprise personal twist, and how everyone else moves on. But given that Endgame also wraps up 22 previous films, it gets a little more leeway than most.

TO SUM UP

While no one should read this blog post as a blueprint to writing a commercial film, the three-act structure is a solid set of guidelines to crafting a screenplay. As one screenwriting professor once told me, “Memorize this, then forget it.” What he means is, allow the structure to become second nature so you start thinking of all of your stories this way, but then don’t worry if you have to have an exception or form-breaker here and there.

Here it all is again in outline form…

Act One (0-25%)

*Background, exposition: Where we see our characters before the story starts.

*Inciting Indident: The item that starts the story.

*Act One Break: The point where the hero decides to leave their comfortable world and launch the journey that will come to define the rest of the movie.

Act Two (25-75%)

*”Holy Shit” moment: A near-immediate reversal of the Act One Break that amps up the anticipated conflict and struggles for the hero.

*Midpoint: Usually a point where the main character has a significant conflict that forces them to double-down on their mission and/or amps up the stakes. If using the “split second act” model, the break between 2A and 2B.

*Act Two Break: Often called the “Dark Night of the Soul” or the “All is Lost” moment. When the hero thinks they’ve failed. Sometimes they return to their old lives, sometimes they have no place else to go.

Act Three (75-100%)

*Reversal: Something that convinces your character that there is still hope after all, and launches them on the final stage of their quest. Quickens the pace of the story.

*Climax: The culmination of the story. The final battle, where the hero must marshall everything they’ve learned throughout the film and go beyond what they could’ve done before.

*Resolution/denoument: Optional, but often employed. Showing what happens after.